One of the fundamental questions in conflict today is simply, “How do we develop a state that is strong enough to deter rebels and attackers while assuring the citizens that its power will not be used for ill?” This problem has reared its head in Iraq, Ukraine and now…the U.S.

One of the fundamental questions in conflict today is simply, “How do we develop a state that is strong enough to deter rebels and attackers while assuring the citizens that its power will not be used for ill?” This problem has reared its head in Iraq, Ukraine and now…the U.S.

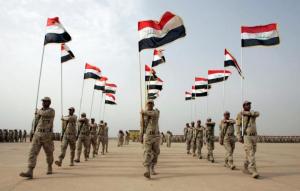

The fundamental problem in Iraq is not the government did not have enough coercive power but that the governors were using that power against the Sunnis. The Iraqi government could have assured the Sunni population that force would only be used against those that opposed the government. Instead, promises were broken and the focus was on exerting dominance, which the reduced both the capacity and legitimacy of the army. The Sunnis who had joined with the U.S. in 2007 have now opted with the Islamic State.

The balance of power has shifted in Ukraine conveniently after the Presidential election as the government has begun to do a better job of assuring the people of Ukraine that they will only harm those who are fighting the government. The use of violence is not as selective as it could be but to many people the government has begun to seem like a better option.

The Israel-Gaza is an extremely complicated conflict but one clear aspect is the difficulty of balancing deterrence and assurance. Hamas as shown little interest in promising Israel anything and Israel insists its only trying to deter attacks. Whether or not you believe this to be true one of the factors of deterrence is that status quo must seem attractive. There must be something to go back to. After all deterrence is both a threat and a promise…”If you do nothing bad, nothing bad will happen to you.” Or, “if you stop we can go back to the status quo”…but what if I don’t like that status quo?

Democracy is often touted as a solution to this problem however even democracies struggle with this balance. The situation in Ferguson illustrates this very well where protests and riots have broken out over the killing of a young African-American male. Police need to have the capability to use force but that force needs to be backed with legitimacy. Furthermore the pattern in the U.S. suggests that the wrong kind of discrimination was at work in Ferguson. Rather than being discriminate in their use of force the police seems to be targeting people on the base of race as in New York.

This is why due process is so vital to a legitimate state. Due process is not just about justice…but also about being careful that the targets of state power are deserving. Like Democracy, due process is not perfect…some innocents are convicted and some guilty go free. But it is much better than when the use of violence is applied wholesale and unfairly by the state.